Las temperaturas medias anuales siguen aumentando sin

control debido al cambio climático. Es en las regiones polares donde el clima está

cambiando de forma más alarmante.

Para ello varios investigadores se han centrado en estudiar

diversos aspectos que nos van a ir desentrañando un pasado muy lejano de hace

69,5-68,5 M.a. correspondientes al límite

Cretácico-Paleógeno. En el cual, se

produjo un aumento del CO2 que aumento las temperaturas provocando

que los climas templados subieran a latitudes mas elevadas a las actuales como

Alaska.

Ilustración 1: A) afloramiento a lo largo del río Colville que

contiene la ubicación de la sección medido La imagen incluye la ubicación de la

cama de bivalvos y las interpretaciones paleoambientales de los estratos

subyacentes y lo recubre con Nucula aff in situ . N. percrassa Conrad encontró en 4,25 m por encima

de la referencia de base (imagen insertada). B)

Paleogeography del área de estudio en la vertiente norte de los arroyos se

ancestral

El lugar escogido es la Formación Prince Creek (FPC) que se

encuentra en Alaska en la que analizando las diferentes rocas y las estructuras que estas contienen

cobrando gran importancia la Siderita se ha deducido como una zona de

desembocadura de arroyos hacia el antiguo mar clyde de poca profundidad.

Todo

ello gracias a unas insignificantes conchas de las especies Nuluca y Noculana y de los dientes de dinosaurios (Suárez et al, 2013.) que nos han permitido saber mediante el análisis isotopico de salinidad del

aragonito,el fosfato, la calcita que la desembocadura de este rió era en forma

de estuario, debido a que lo niveles de salinidad eran inferiores a los del mar

teniendo

como referencia minerales de aragonito de Aragón de España y calcita del Condado de Big Horn, Montana

Pero

no se queda hay todo gracias a las especies N.

Percrasa y N. Ancilata podemos

analizar el crecimiento como los anillos del tronco de un árbol. En los cuales

cada banda coincide con la época de desove y con las maximas temperaturas. Que

junto a los datos y registros vegetales-florares de Spicer y Herana (2010) se estimaban temperaturas de

-2Cº a 14,5Cº.

Pero esto anillos también

nos indican la edad que es de 5 años por anillo En el caso de N. annulata. Los especímenes de mayor tamaño son difíciles

de estimar ya que la distancia de los anillos disminuye.

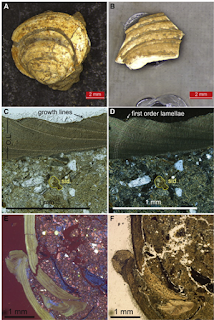

Ilustración 2: Fotos y

microfotografías de Nucula C) microfotografía plena luz

polarizada que muestra las líneas distintas de crecimiento (seleccionar líneas

de crecimiento señalados por las líneas de puntos blancos) Un pequeño

nódulo siderita pedogénico también se expone (sid. = Siderita.) D) microfotografía luz polarizada

transversal que muestra la misma región y laminillas de primer orden

(laminillas seleccionada se indica por líneas de puntos blancos). E) Llanura microfotografía luz

polarizada de los bivalvos que muestran capas de crecimiento. F) La misma región en C bajo

cátodoluminiscencia sin mostrar recristalización de aragonito antigénico.

Estas

variaciones tan grandes hacen que los ríos y arroyos estén influenciados por la

cantidad de nieve. Que a su vez condicionaron un clima mas húmedo y cálido de

veranos suaves que sustente un ecosistema templado que sustento dinosaurios,

mamíferos y una rica amplia variedad de flora.

Por

ello el estudio de los diferentes fósiles y minerales pone de manifiesto la

importancia de utilizar diversos un enfoque grupos taxonómicos para reconstruir

la paleohidrologia y el paleoecosistema.

Ilustración 3: La reconstrucción paleoambiental

del bajo delta Cretácico por la cuesta lisa del norte de Alaska

Así

sera el Futuro. Así que yo si fuera vosotros iría haciendo las maletas.

Referencias:

Ansell, A.D., 1974. Seasonal changes in biochemical composition of the bivalve Nucula sulcata from the Clyde Sea area. Mar. Biol. 252, 101–108.

Arthur, M.A., Williams, D.F.,

Jones, D.S., 1983. Seasonal temperature–salinity changes and thermocline development in Mid-Atlantic Bight as

recorded by the isotopic composition of bivalves. Geology 11, 655–659.

Besse, J., Courtillot, V., 1991. Revised and synthetic apparent polar wander paths of the African, Eurasian, North American and Indian plates, and

true polar wander since 200 Ma. J. Geophys. Res. 96, 4029–4050.

Brey, T., Mackensen, A., 1997. Stable isotopes prove shell growth bands in the Antarctic bivalve Laternula

elliptica to be formed annually. Polar Biol. 17, 465–468.

Brouwers, E.M., De

Deckker, P., 1993. Late Maastrichtian and Danian ostracode faunas from northern Alaska: reconstructions of environment and

paleogeography. Palaios 8, 140–154.

Burns, W.M., Hayba, D.O.,

Rowan, E.L., Houseknecht, D.W., 2005. Estimating the amount

of eroded section in a partially exhumed basin from geophysical well logs: an example from the North Slope. U.S. Geol. Surv. Spec. Pap. 1732-D, 1–18.

Dutton, A., Wilkinson, B.H.,

Welker, J.M., Bowen, G.J., Lohmann, K.C., 2005. Spatial distribution and seasonal variation in 18O/16O of modern precipitation and river water across the conterminous USA. Hydrol. Process. 19,

4121–4146.

Eberle, J.J.,

Greenwood, D.R., 2012. Life at the top of the greenhouse Eocene world—a review of the Eocene flora and vertebrate fauna from Canada's High Arctic. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 124, 3–23.

Fiorillo, A.R., McCarthy, P.J., Flaig, P.P.,

2010. Taphonomic and sedimentologic interpreta- tions of the dinosaur-bearing Upper Cretaceous Strata

of the Prince Creek Formation, Northern Alaska: insights from an ancient high-latitude

terrestrial ecosystem. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 295, 376–388.

Flaig, P.P.,

Fiorillo, A.R., 2015. Dinosaur-bearing hyperconcentrated flows of Cretaceous arctic Alaska: recurring catastrophic event beds on a

distal paleopolar coastal plain. PALAIOS 29, 594–611.

Flaig,

P.P., McCarthy, P.J., Fiorillo, A.R., 2011. A tidally influenced, high-latitude coastal plain: the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Prince Creek

Formation, North Slope, Alaska. In: Davidson, S., Leleu, S., North, C. (Eds.),

From River to Rock Record: The Preservation of Fluvial Sediments and their Subsequent

Interpretation. SEPM Special Publication 97, pp. 233–264.

Flaig, P.P., McCarthy, P.J., Fiorillo, A.R., 2013. Anatomy, evolution and paleoenvironmental interpretation of an ancient arctic coastal plain:

Integrated paleopedology and palynology from the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian)

Prince Creek Formation, North Slope, Alaska.

In: Driese, S.G., Nordt, L.C. (Eds.), New Frontiers in Paleopedology and Terrestrial Paleoclimatology.

SEPM Special Publications 104, pp. 179–230.

González, L.A., Lohmann, K.C., 1985. Carbon and oxygen

isotopic composition of Holocene reefal carbonates. Geology

13, 811–814.

Grossman, E.L., 2012. Applying oxygen isotope

paleothermometry in deep

time. In: Ivany, L., Huber, B.T. (Eds.), Reconstructing Earth's Deep-Time Climate—The State of the Art in 2012, Paleontological Society

Short Course, November

3, 2012. The Paleontological Society Papers 18, pp. 39–67.

Grossman, E.L., Ku, T.-L., 1986. Oxygen and carbon isotope fractionation in biogenic aragonite: temperature effects. Chem. Geol. Isot. Geosci.

59–74.

Huber, B.T., 1998. Tropical paradise at the Cretaceous poles. Science 282,

2199–2200. Jahren, A.H., Sternberg, L.S.,

2008. Annual patterns within tree rings of the Arctic middle

Eocene (ca. 45 Ma): isotopic signatures of precipitation,

relative humidity, and deciduousness. Geology 36, 99–102.

Jones, D.S., Arthur, M.A., Allards, D., 1989. Sclerochronological records of temperature and growth from shells of Mercenaria mercenaria from Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island. Mar. Biol. 102, 225–234.

Killingley, J.P., Berger, W.H., 1979. Stable isotopes in a mollusk

shell: detection of upwell- ing events. Science

205, 186–188.

Markwick, P.J.,

1998. Fossil crocodilians as indicators of Late Cretaceous and

Cenozoic climates: implications for using

palaeontological data in reconstructing palaeoclimate. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol.

137, 205–271.

McClelland,

J.W., Holmes, R.M., Dunton, K.H., Macdonald, R.W., 2012. The Arctic Ocean estuary. Estuar. Coasts 35, 353–368.

Meissner, P., Mutterlose, J., Bodin,

S., 2015. Latitudinal temperature trends

in the northern hemisphere during the Early Cretaceous (Valanginian–Hauterivian). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 424, 17–39.

Nordt, L., Atchley, S., Dworkin, S., 2003. Terrestrial evidence for two greenhouse events in the latest Cretaceous. GSA Today 13, 4–9.

Norris, R.D., Bice, K.L.,

Magno, E.A., Wilson,

P.A., 2002. Jiggling the tropical

thermostat in the Cretaceous hothouse.

Geology 30, 299–302.

Nunn, E.V., Price,

G.D., Gröcke, D.R., Baraboshkin, E.Y., Leng, M.J., Hart, M.B., 2010. The Valanginian positive carbon isotope event in Arctic

Russia: evidence from terrestrial and marine isotope records and implications for global

carbon cycling. Cretac. Res. 31, 577–592.

Phillips, R.L., 2003. Depositional environments and processes in Upper

Cretaceous nonmarine and marine sediments, Ocean Point dinosaur

locality, North Slope,

Alaska. Cretac. Res. 24, 499–523.

Rich, T.H., Vickers-Rich, P., Gangloff, R.A., 2002. Polar dinosaurs. Science 295, 979–980. RRUFF database, 2013. A Website Containing an Integrated Database of Raman

Spectra, X-

ray Diffraction and Chemistry Data for Minerals by the

University of Arizona, rruff.info, checked August 30, 2013.

Schöne, B.R., Surge, D., 2012. Part N, Revised,

Chapter 14. Bivalve

schlerochronology and geochemistry. Treatise Online 46. University of Kansas,

Paleontological Institute, pp. 1–24.

Schubert, B.A.,

Jahren, A.H., Eberle,

J.J., Sternberg, L.S.L.,

Eberth, D.A., 2012. A summertime rainy season in the Arctic forests of the Eocene.

Geology 40, 523–526.

Spicer, R.A.,

Herman, A.B., 2010. The Late Cretaceous environment of the Arctic: a quantitative reassessment based on plant fossils.

Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 295, 423–442.

Suarez, C.A.,

Ludvigson, G.A., Gonzalez, L.A., Fiorillo, A.R., Flaig, P.P., McCarthy, P.J.,

2013. Use of multiple oxygen isotope proxies for elucidating Arctic Cretaceous

Palaeo- hydrology. In: Bojar, A.-V., Melomte-Dobrinescu, M.C., Smit, J.

(Eds.), Isotopic Studies in Cretaceous Research. Geological

Society of London, Special Publications 382.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1144/SP382.3.

Suarez, M.B., Gonzalez, L.A., Ludvigson, G.A., 2011. Quantification of a greenhouse hydro- logic cycle from equatorial to polar latitudes: The

mid-Cretaceous water bearer revisitied, Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology. Palaeoecology 307, 301–312.

Surge, D., Lohmann,

K.C., Dettman, D.L., 2001. Controls on isotopic chemistry of the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica: implications for growth

patterns. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 172, 283–296.

Torres, M.E., Zima,

D., Falkner, K.K., MacDonald, R.W., O'Brien, M., Schöne, B.R., Siferd, T.,

2011. Hydrographic changes in Nares Strait (Canadian Arctic

Archipelago) in recent decades based on δ18O profiles of

bivalve shells. Arctic 64, 45–58.

Tripati, A., Zachos,

J., Marincovich, L., Bice, K., 2001. Late Paleocene Arctic coastal climate inferred from molluscan stable and radiogenic isotope

ratios. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 170, 101–113.

U.S. National

Ocean Survey, 1970. Surface water temperature and density. Pacific Coast, North and South America, and Pacific Islands. National Ocean Survey Publication, United States Department of Commerce, Washington D.C, pp. 31–33.

Ufnar, D.F., González, L.A., Ludvigson, G.A., Brenner, R.L., Witzke, B.J.,

2004. Evidence for increased latent heat transport during the Cretaceous

(Albian) greenhouse warming. Geology 32, 1049–1052.

Urey, H.C.,

Lowenstan, H.A., Epstein, S.,

McKinney, C.R., 1951. Measurement of paleotemperatures and temperatures of the upper Cretaceous of England, Denmark, and the southeastern United

States. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull.

62, 399–416.

van der Kolk, D.A.,

Flaig, P.P., Hasiotis, S.T., 2015. Paleoenvironmental reconstruction of a Late

Cretaceous, muddy, river-dominated polar deltaic system: Schrader Bluff-Prince

Creek Formation transition, Shivugak Bluffs, North Slope of Alaska, USA. J. Sediment.

Res. 85 (8). http://dx.doi.org/10.2110/jsr.2015.58 (in press).

Vince, S.W., Snow,

A.A., 1984. Plant zonation in an Alaskan salt marsh: I. Distribution, abundance and environmental factors. J. Ecol. 72, 651–667.

Wefer, G., Berger, W.H.,

1991. Isotope paleontology — growth and composition of extant calcareous species. Mar. Geol. 100, 207–248.

Witte,

K.W., Stone, D.B., Mull, C.G., 1987. Paleomagnetism, paleobotany, and paleogeography

of the Cretaceous, North Slope, Alaska.

In: Taiileur, I., Weimer, P. (Eds.), Alaska North Slope Geology: The

Pacific Section. Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralo- gists and the Alaska Geological Society 1, pp. 571–579.

Yan, H., Lee, X., Zhou, H., Cheng, H., Peng, Y., Zhou, Z., 2009. Stable isotope composition of the modern freshwater bivalve Corbicula

fluminea. Geochem. J. 43, 379–387.

Zhou, J., Poulsen, C.J., Pollard, D., White, T.S.,

2008. Simulation of modern and middle Cretaceous marine δ18O with an ocean–atmosphere general circulation model. Paleoceanography 23, PA322

1 comentario:

¿Qué investigadores? ¿En qué trabajo? Estos en este:

Suarez, C.A., Flaig, P.P., Ludvigson, G.A., González, L.A., Tian, R., Zhou, H., McCarthy, P.J., Van der Kolk, D.A. & Fiorillo, A.R. 2016. Reconstructing the paleohydrology of a cretaceous Alaskan paleopolar coastal plain from stable isotopes of bivalves. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 441: 339–351

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0031018215003922

También tendrías que repasar los nombres científicos porque hay varias erratas (demasiadas).

Y sólo se han de referenciar los trabajos citados en tu entrada... no todos los mencionados en el trabajo que comentas.

Y sobre las etiquetas... los géneros estudiados son bivalvos, no gasterópodos...

Publicar un comentario